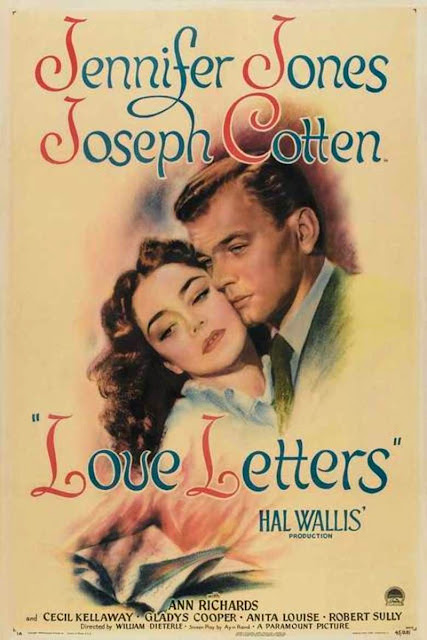

Classic Film of the Week #21: Love Letters (1945)

|

| (image via IMDB) |

It seems that audiences have a special fascination with the kinds of movies that place relatable characters in outrageous situations. These kinds of narratives are especially popular in the romance genre, where we watch unsuspecting couples come up against unbelievable hurdles, and still somehow end up together. But where things become more interesting is when these love stories move past hilariously convoluted misunderstandings or death-defying sci-fi adventure and incorporate real moral dilemmas that present a challenge to the audience. While I have not actually seen the film, I have certainly heard about the controversy over the 2016 film Passengers, in which Chris Pratt's character deceives his love interest, Jennifer Lawrence, in a way that many viewers found to be incredibly disturbing. There's nothing inherently wrong with a film that challenges people--in fact, every good film should strive to do this in one way or another--but it becomes more complex in genres like romance, where a certain outcome is expected, or even demanded, by the audience. How can writers navigate these tricky waters of introducing morally grey elements to a cinematic relationship while still convincing the audience that the inevitable happy ending has been earned by the characters? Over half a century before Passengers, the Jennifer Jones and Joseph Cotten vehicle Love Letters tackled some very similar moral hurdles, and while the results are unsurprising, the film does manage to sell its outlandish premise in a way that's surprisingly compelling.

Love Letters begins by introducing us to two soldiers, one of whom is in love with a girl back home. He spends much of his time sending her love letters; the problem being that these letters are written by his much more articulate friend, Alan (played by Joseph Cotten), who agreed to the ruse as a gag but has now fallen in love with the girl, Victoria, himself. However, he can't bring himself to admit the falsehood to her, and when his friend gets leave he goes home and marries her. Interestingly, this is almost the same premise as the opening of The Harvey Girls, a film I discussed a few weeks ago: Judy Garland originally got on that train in the hopes of marrying the well-spoken man she had been writing to, but when she gets to the town she finds out her suitor is nothing like she had imagined, and the letters were actually written by someone else. Luckily for her, the man has a sense of decency and upon seeing her and realizing the real implications of what he's done, he sets her free from their engagement; Victoria isn't nearly so fortunate, and must endure more than her share of suffering as she tries to figure out why the perfect lover in her beautiful letters is so different when he's standing in front of her. One of the more interesting conundrums of the film surfaces here: who is more in the wrong, Alan for not admitting to writing the letters or his friend for marrying Victoria without telling the truth? Both men have the opportunity to save her from her tragic fate, but choose not to.

When Alan gets out of the army, he still has Victoria on his mind, and resolves to pay her and his old friend a visit. Before he gets the chance, he winds up at a party where he finds himself drawn to a lovely, mysterious young woman named Singleton (played by Jennifer Jones). As he digs deeper into who she is, he discovers that she's actually Victoria, stricken with amnesia ever since the violent death of her husband--that she's supposedly responsible for. The trauma erased from her memory, she's the bright and enthusiastic woman from her letters, and finally united in person the two quickly fall for each other. Here is where the real moral quandary arises: is it right for him to pursue a romance with Singleton, knowing who she is and how she might be hurt if her memory ever returns? The interesting thing about the film is how much blame it places on Alan for what's happened to Victoria; in many scenes it actually seems to hold him more responsible than his friend, arguing that he's a better man than the friend was and therefore had a moral responsibility to step in before anybody got hurt. Strangely, it is this heavy-handed placing of blame on Alan that actually creates the moral issue; otherwise, I think most viewers would see Alan as a mostly innocent party and wouldn't even question his affair with Singleton.

Because Joseph Cotten and Jennifer Jones are truly a magnificent screen-pairing, with a natural chemistry that grounds the often outrageous stories their characters exist within. No matter what melodramatic insanity is going on around them, you believe in the connection they share, and the idea that they were made for each other. Singleton is quite similar to Jennie in last week's film, The Portrait of Jennie, in that she's quite childlike and emotionally dependent on Cotten--yet the relationships never come across as inappropriate because Cotten is not patronizing or controlling of her. While in both films he has knowledge of her situation that he keeps from her, he doesn't do this to gain power over her, but because he has no choice: the consequences of telling her could lead to her own destruction. It's a delicate balance, and one that others may interpret less favorably, but I can't help but appreciate what these two actors were able to accomplish in these two films, especially Love Letters where the love story is less allegorical and more hands-on, with the pair actually marrying and building a life together. There's a number of effective scenes as Singleton comes into her own as a woman and discovers the beauty of life she's been missing out on, and you get the sense that this transformation may not have been possible without Alan's decision to carry on the romance--while her friends and family loved her, it's almost as if their caution was stifling her, preventing her from becoming a real person again.

On the whole, I found Love Letters to be a highly enjoyable and compelling romantic melodrama, one of the best I've seen from this era. Not surprisingly, the one place where it falters is in the ending: despite the film's willingness to engage with complex moral issues up to this point, by the end it seems to have grown tired of them and goes for the cliche Hollywood conclusion. While a happy ending is appropriate for the film, the simplistic nature of this one just doesn't quite fit what came before. But even though Love Letters doesn't quite stick the landing, ultimately I think it's a fine example of Hollywood melodrama at its convoluted--and romantic--best.

Love Letters comes recommended.

|

| (image via Alchetron) |

Comments

Post a Comment